“Take The Hardest Path” – Roberto Rossellini’s “Voyage to Italy”

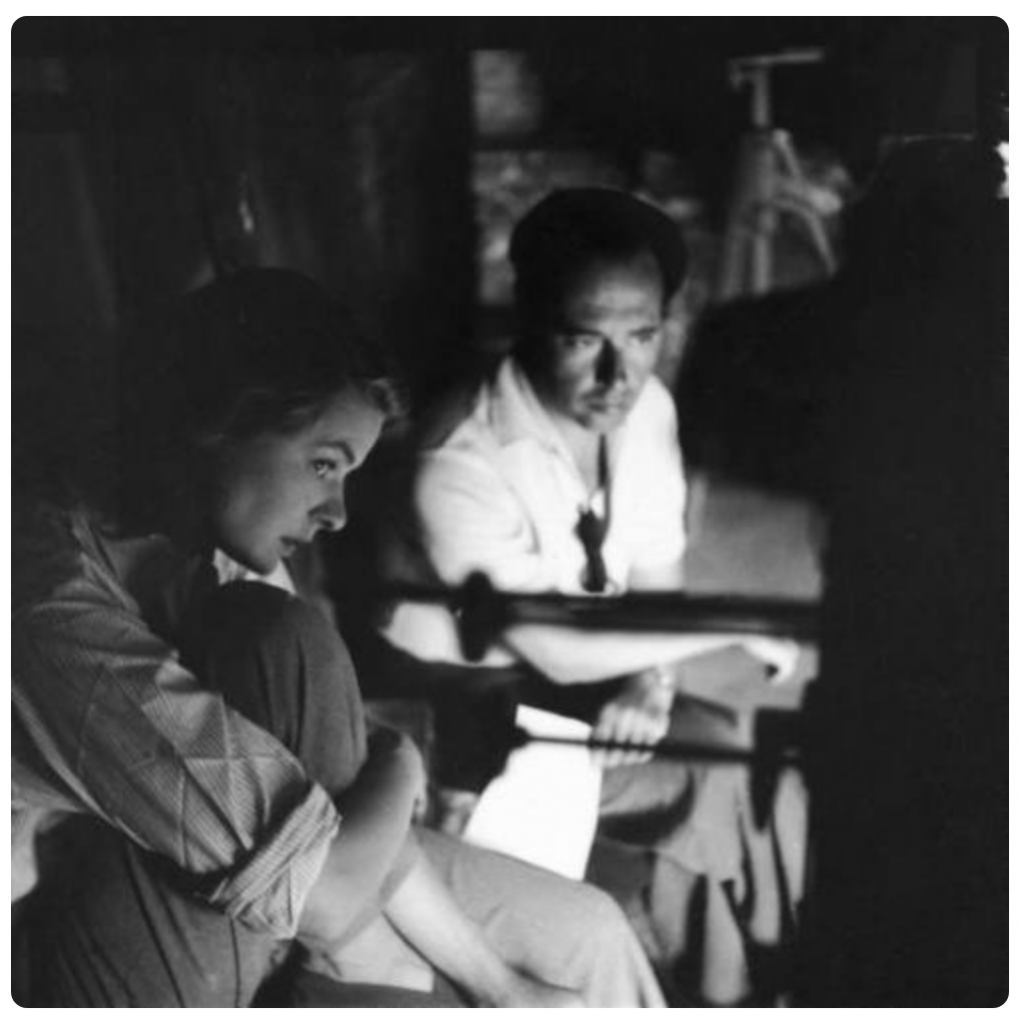

In July 2009, I wrote in Senses of Cinema about Rossellini’s remarkable Voyage to Italy that the film “was shot from 2 February through 30 April 1953, on a variety of locations throughout Italy, including Naples, Capri, Pompeii, and at the Titanus studios in Rome, and was a tempestuous production throughout. The plot is simple: an unhappily married couple, Katherine (Ingrid Bergman) and Alex Joyce (George Sanders) are traveling from London through Italy to Naples, where they have inherited a villa.

Their marriage is a shambles, and they quarrel constantly; indeed, it is hard to imagine a more ill suited couple in the history of cinema. Katherine, relatively young and vibrant, seems trapped in a loveless match with the ill-tempered, dour Alex, who thinks only of money, and openly flirts with other women while ignoring his wife. Katherine has made the journey not only to sell the villa, but also in the hope that the “voyage” will reignite the passion of their marriage; instead, as the trip becomes more complex, and fraught with delays and interruptions, Alex’s boredom and frustration turns to outright hostility towards his wife.

In desperation, Katherine recounts to her disaffected husband the tale of a former suitor who, long ago, has been passionately in love with her; but Alex is unmoved, and Katherine seems resigned to the fact that their marriage will end in divorce, as soon as the necessary papers for the sale of the villa have been signed. The couple decide to split up, and spend their remaining time in Naples separately; Katherine visits a series of natural wonders with a succession of paid, only professionally attentive Italian tour guides, while Alex seeks out the company of a group of British nationals vacationing in Capri.

Katherine’s time is nevertheless redolent of the state of her collapsing marriage; viewing the ruins of Pompeii, with human bodies still entombed in centuries-old ash, as well as witnessing first-hand a small volcanic eruption on a tour, Katherine seems lost, lonely, and disconnected from the world around her, yet at the same time she years for some sort of human compassion. Alex is clearly disinterested.

And yet, in the film’s final, unforgettable sequence, as the now-reunited, but still-quarreling couple watch a passing religious procession, they are seized with an unexpected emotion, and fervently embrace each other, declaring their love, and wondering how they could possibly have become so estranged. Their renewal of love is a miracle, entirely inexplicable by any conventional narrative standards; the entire film, indeed, has been consistently moving away from such a reconciliation.

Love appears to have conquered a seemingly irreparable emotional breakdown. It is one of the most unexpected and transcendent moments in not just all of Rossellini, but in all of cinema; as one might imagine, the ending was also highly controversial at the time of the film’s release, and remains so, because it seems to come out of thin air, rather than in response to any section or aspect of the film’s narrative exposition.”

Much of the film was improvised; often Rossellini didn’t really know which direction the film was going in. The actors, especially George Sanders, were often irritated by Rossellini’s seeming indecision during the production, but the director was searching for something through the film, something perhaps related to his difficult and ultimately doomed relationship with Ingrid Bergman, who worked with Rossellini in three of his films, and abandoned her Hollywood career to work with him in Italy.

As I observed back in 2009, “Voyage to Italy is a film in search of itself, a film that only knows its own conclusion when it appears, miraculously, in front of it, arriving at a final destination that no one in the audience could possibly have foreseen. And yet, the final moments of the film seem absolutely ‘right’; indeed, it seems to be the only possible conclusion to the film.” And yet this could not have been an easy path to take; rather, it was a jump into the void, with only the slightest idea of how the film would finally end. And yet only with such a quest can anything worthwhile be made; if you aren’t searching for something, then you are lost.

“When you don’t know which path to take, choose the hardest one.” – Roberto Rossellini

Tags: Discovery, Experimental Cinema, Film Business, Film Criticism, Film History, Foreign Films, independent feature films, Ingrid Bergman, Italian Cinema, Robert Rossellini, Senses of Cinema, Voyage to Italy, Wheeler Winston Dixon

This entry was posted on Tuesday, August 8th, 2017 at 3:18 pm and is filed under Criticism, Experimental Cinema, Film Business, Film Criticism, Film History, Foreign Films, History, Humanities, Inside Stuff, Publishing, Reviews. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. Both comments and pings are currently closed.

Fuente: http://blog.unl.edu/dixon/2017/08/08/take-the-hardest-path-roberto-rossellinisvoyage-to-italy/